Indian American Siblings Developing Better Functionality for Prosthetics

While Eeshan, an electrical engineering and computer science major, initially wanted to build his own prosthetic, the siblings quickly realized that the actual problem wasn’t a lack of prosthetics, but rather, no one was focused on making them easier to control.

FREMONT, CA: Previously, after a friend of the Indian American siblings had their hand amputated, they witnessed the challenges of living with a prosthetic, and that, too, with one that performed unreliably. Eeshan says it was “like giving someone the world’s greatest computer, but with a broken keyboard and mouse,” an MIT report said.

Frustrated by how this exorbitantly expensive device could lack such basic functionality, he and his sister set out to find a better solution. While Eeshan, an electrical engineering and computer science major, initially wanted to build his own prosthetic, the siblings quickly realized that the actual problem wasn’t a lack of prosthetics, but rather, no one was focused on making them easier to control.

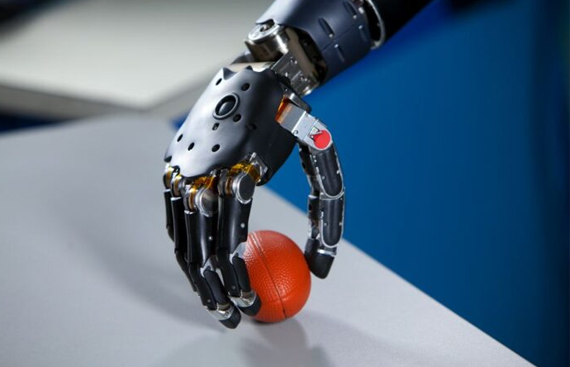

By combining their understanding of amputees’ struggles with Vini’s technical background in neuroengineering and Eeshan’s experience in computer engineering, the two began working to develop a low-cost, non-invasive, brain-controlled interface that could improve the functionality of existing prosthetics limbs. Before long, they had designed a neuroprosthetic interface that couples electromyograph and electroencephalograph sensors with a proprietary algorithm to restore natural functionality to amputees, according to the report.

“We’re building a device that decodes your muscle and brain signals and translates them into commands that a prosthetic hand can use to make gestures and grasp objects. We aren’t building the prosthetic hand; we’re building the interface that controls the hand, and we’re doing it completely non-invasively,” Eeshan said in the report.

The Tripathiis decided that starting a company would help move their idea forward. So they turned to the MIT Sandbox Innovation Fund Program for support and guidance, which connected them with mentors who helped the siblings shape their long-term research and development strategy and craft a polished pitch, the report said.

When the COVID-19 pandemic struck in 2020, eliminating critical access to labs at MIT and Cornell Tech, where Vini was a student, seed funding from MIT Sandbox allowed them to continue developing their product from their home in New Jersey, it said. And from there, Invictus BCI Incorporated was created. Since then, Eeshan and Vini have made significant progress and are closer to their goal of bringing their technology to market as a solution for amputees.

“I have found that the moment you start working on something that people need, rather than something people want, it becomes impossible to work purely for yourself,” Eeshan added in the report. “Your motivation grows beyond a personal desire to create a solution.”